Fear, stress, and anxiety are some of the biggest dangers to our mental health. But like many of our unpleasant emotions, they have important functional origins; without them, we lack the motivation to flee from danger or avoid harmful behaviors.

The amygdala is a brain structure involved in emotional experiences, such as fear and anxiety. Stressful experiences can adjust its sensitivity. For soldiers who enter military service, for example, symptoms of stress correlate with their amygdala reactivity. After their military service, their amygdala is more responsive to medical images than it was before their service started.

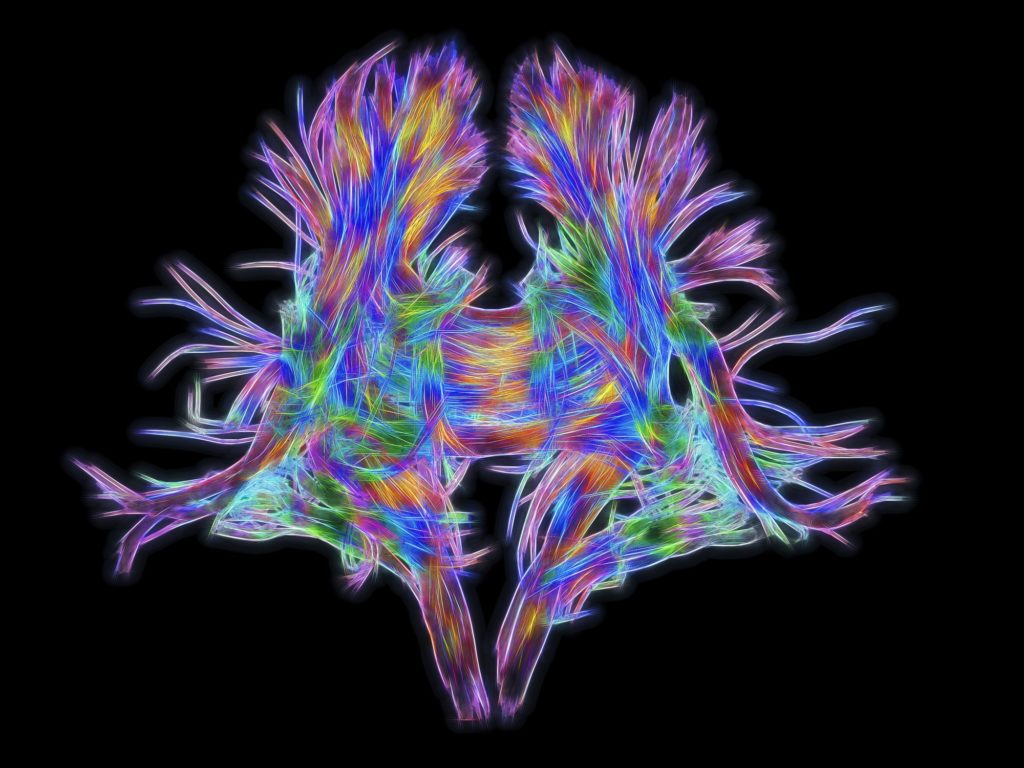

Some evidence suggests that our brain’s prefrontal cortex, an area frequently linked to behavioral control and decision-making, regulates the level of activity in our amygdala when we are faced with unpleasant stressors. Patients with lesions in specific parts of their prefrontal cortex show stronger amygdala responses when looking at distressing images. In a sense, their amygdalae are out of control. Other abnormalities in this control link between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala are characteristic of patients who suffer from depression.

This raises an interesting question: Could we help people deal with stress by training them to control the activity in their amygdala when they are feeling anxious?

One neuroscience technique known as neurofeedback may provide an answer. The general objective behind the technique is to teach people to recognize signals that reflect what their brain is doing and react accordingly. Imagine a computer that shows you a ball moving to the left or right, depending on how active your left or right motor cortex is. Or a computer that rewards you with money every time it detects unconscious brain activity connected to your phobia of snakes. If the computer manages to build a positive rather than negative association to a particular stressor within your brain, it could ultimately reduce your reactions of panic when you encounter that stressor in the real world. This approach has already shown promise in curing phobias.

Many existing treatments for these problems require people to relive specific fears, which obviously can be a painful and difficult process.

A study published in early 2019 tested whether neurofeedback could improve amygdala control in the brains of soldiers. The researchers recruited a total of 180 soldiers who were in the first few weeks of a stressful combat training program designed to ready them for deployment. They assigned half of that group — 90 soldiers — to a training course of amygdala neurofeedback.

This neurofeedback aimed to train their brains to better regulate amygdala activity. To achieve this, the soldiers watched an animation of a hospital waiting room with a few agitated characters shouting at a receptionist. The soldiers were told to “find the mental strategy” that would make those characters calm down. The instructions were intentionally vague, and soldiers knew little about what was going on in their brain. But if they successfully suppressed the level of activity in their amygdala, the characters on the screen would calm down.

In other words, over the course of the neurofeedback training program, these 90 soldiers watched the video, played around with their minds until the characters calmed down, and then tried to repeat the mental strategies that achieved that goal. A brain monitor behind the scenes looked for an electrical fingerprint related to the amygdala and calmed the characters whenever it detected declining activity in that fingerprint.

To know for sure that their neurofeedback was working specifically for the amygdala, the researchers assigned the remaining 90 soldiers in their sample to a control group. This group either trained with neurofeedback using an irrelevant brain signal outside the amygdala or participated in no neurofeedback whatsoever.

Soldiers completed a total of six neurofeedback sessions over four weeks at their military training base. The main question was whether the amygdala group would develop better emotion-regulation skills than the control group after training was completed.

During the neurofeedback itself, the researchers found exactly what they expected. According to the brain activity data, the soldiers in the amygdala neurofeedback group reduced their amygdala activity more than the soldiers in the control group, at least after their fourth session of training.

When the researchers removed the hospital animation and simply asked the amygdala neurofeedback soldiers to recreate the mental strategy they had picked up, the soldiers were able to successfully suppress their amygdala on demand while looking at a blank screen. In fact, they could achieve the same feat while simultaneously focusing on a separate memory task. So, even when people were under mental pressure, they could apply the strategies they learned through neurofeedback.

Going a step further, the researchers tested whether these amygdala changes would translate into better emotion control. In a behavioral test that measured how well people could categorize emotions on faces while being distracted by inconsistent emotional words, soldiers in the amygdala neurofeedback group were better able to prevent the distraction from interfering with their performance.

Using some additional questionnaires, the researchers also found that after amygdala neurofeedback, soldiers could more effectively identify and describe their own emotions. More specifically, compared to the control group, they showed larger reductions in scores related to a trait known as alexithymia, which refers to a difficulty in understanding our personal emotional states.

During the neurofeedback training at the military camp, the researchers used a brain-monitoring method known as electroencephalography, primarily because the equipment is mobile and practical. However, this method could detect only an indirect electrical fingerprint for the amygdala, rather than a reliable and direct signal coming from the amygdala itself. Although past evidence suggests a good link between this electrical fingerprint and more spatially precise brain scans, the researchers wanted to confirm that their neurofeedback had targeted the intended brain areas.

For that reason, in an important final test, the researchers brought 30 of the amygdala neurofeedback soldiers and 30 of the control group soldiers back to an academic lab one month after the training sessions ended. The soldiers entered a functional magnetic brain-imaging scanner — a more precise method for assessing where brain activity is coming from — and ran through another neurofeedback protocol. As expected, the soldiers who had undergone amygdala neurofeedback training at their military camp were better able to reduce their amygdala activity than soldiers in the control group.

This final brain-imaging test allowed the researchers to test the interactions between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala. The researchers found stronger connectivity between these two areas of the brain among the soldiers trained with amygdala neurofeedback compared to the soldiers in the control group.

So, this follow-up brain scanning, a whole month after the neurofeedback training, suggested that the program’s success may have relied on strengthening the circuit between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala. But perhaps more important, it also highlighted that the training benefits lasted several weeks at the very least.

If there is one thing about neurofeedback that should excite us, it is the ability to influence the core brain systems underlying stress and anxiety without necessarily exposing people to their dreaded fears in the process. Many existing behavioral and psychological treatments for these problems require people to relive specific fears, which obviously can be a painful and difficult process.

Although it is still early days in the neurofeedback world, the research continues to expand and surprise us. As brain-imaging technology becomes more practical, more precise, and more widely available, we could all have the opportunity to use it in enhancing our ability to cope with stress. One of the biggest challenges to our emotional well-being is our tendency to impulsively overreact when we come across a new challenge. Although we cannot yet find reliable at-home neurofeedback tools to improve our resilience and self-control, we are arguably moving in that direction.

Until then, the research is a great reminder of how quickly our brains can adapt to helpful feedback and practice. We may be able to harness those qualities by creating our own feedback systems that make it immediately clear when we behave in a way we want to avoid. If we often regret feeling angry, perhaps we can invent an “alarm word” with our friends and partners that they use in snapping us out of our impulsive emotional cycles. Or perhaps, like many great athletes, we can practice rituals and habits that we associate with feeling focused and confident so we can use them when we become anxious or distracted. Superstitions may often seem bizarre and even factually absurd, but they also seem to help us.

Of course, we should never forget the utility of uncomfortable emotions. When we are optimistic about anxiety — when we accept that it helps rather than harms our performance by focusing our attention on important goals — we increase our chances of success. A little psychological pressure can infuse critical events in our lives with the emotional weight they deserve—but too much can debilitate us. It is in this latter case where neurofeedback could become our lifeguard.

This blog is a repost from: https://onezero.medium.com/how-neurofeedback-is-revolutionizing-stress-management-3e0cac041e1 – All credit belongs to “OneZero” and Erman Misirlisjoy, PhD